Africa’s Development Crisis: A Demographic Burden or the Price of Corruption and Bad Governance?

Africa’s slow economic progress since the wave of independence in the 1960s has often been blamed on a multitude of factors. While demography undoubtedly plays a structural role, to understate the corrosive effects of bad governance and endemic corruption is to miss the heart of Africa’s development crisis.

According to the World Bank’s 2024/25 classification, 22 African countries remain low-income and 24 are classified as lower-middle-income. This makes Africa the most underdeveloped region globally, despite having received over US$2.3 trillion in development assistance since independence. The persistence of poverty and underdevelopment amid such vast financial inflows raises a fundamental question: Where has the money gone?

The answer, too often, lies in corrupt leadership, weak institutions, and state capture by political elites. These systemic issues have undermined infrastructure development, weakened education and healthcare systems, and diverted resources away from productive sectors into private pockets.

Demographics: A Real Challenge, But Not the Only One

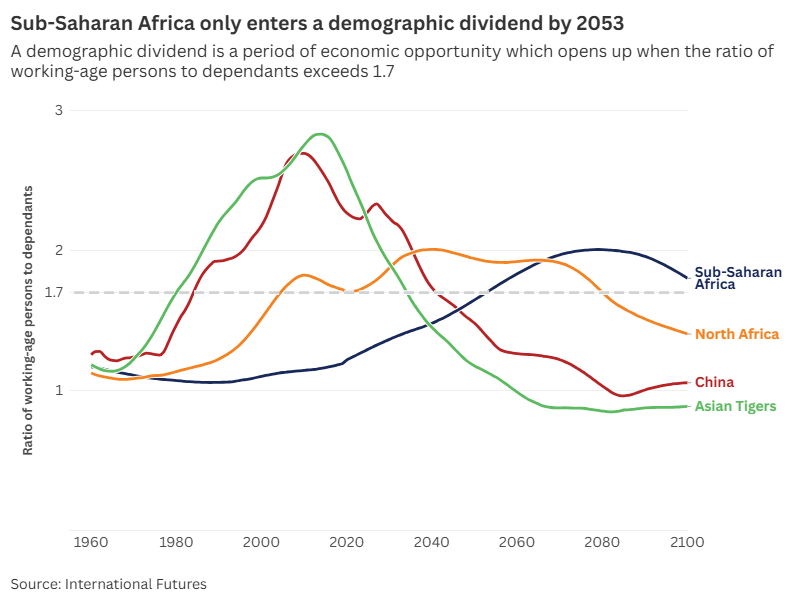

It is true that Africa’s high dependency ratios – where one working-age individual supports almost an equal number of dependents – have placed a heavy strain on economic growth. In the 1960s, the continent had nearly a 1:1 ratio between working-age adults and dependants. Although this began to improve after the 1980s, even by 2025, the ratio stands at a modest 1.3:1 – still far from the 1.7:1 “demographic dividend” threshold where labour significantly boosts economic growth.

But demographic burdens alone cannot explain why many African countries have failed to translate youthful populations into economic strength. Other nations – like China and the so-called Asian Tigers – managed to turn demographic change into a launchpad for prosperity. How? Through strong governance, strategic policy-making, investment in education, and disciplined use of aid and domestic resources.

Where Governance Fails, Poverty Thrives

Unlike the Asian Tigers or China, African countries have been plagued by poor leadership that has failed to make the necessary investments in education, healthcare, and economic transformation. Corruption at the highest levels of government siphons billions away from essential services every year. Political instability and short-termism have resulted in inconsistent policies, failed reforms, and economies that rely heavily on subsistence agriculture and informal trade.

Consider Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country. Despite its vast oil wealth, it continues to struggle with power outages, poor road networks, dilapidated schools, and a healthcare system in crisis. The reason is not demography – it’s decades of looting, policy failure, and elite capture of state resources.

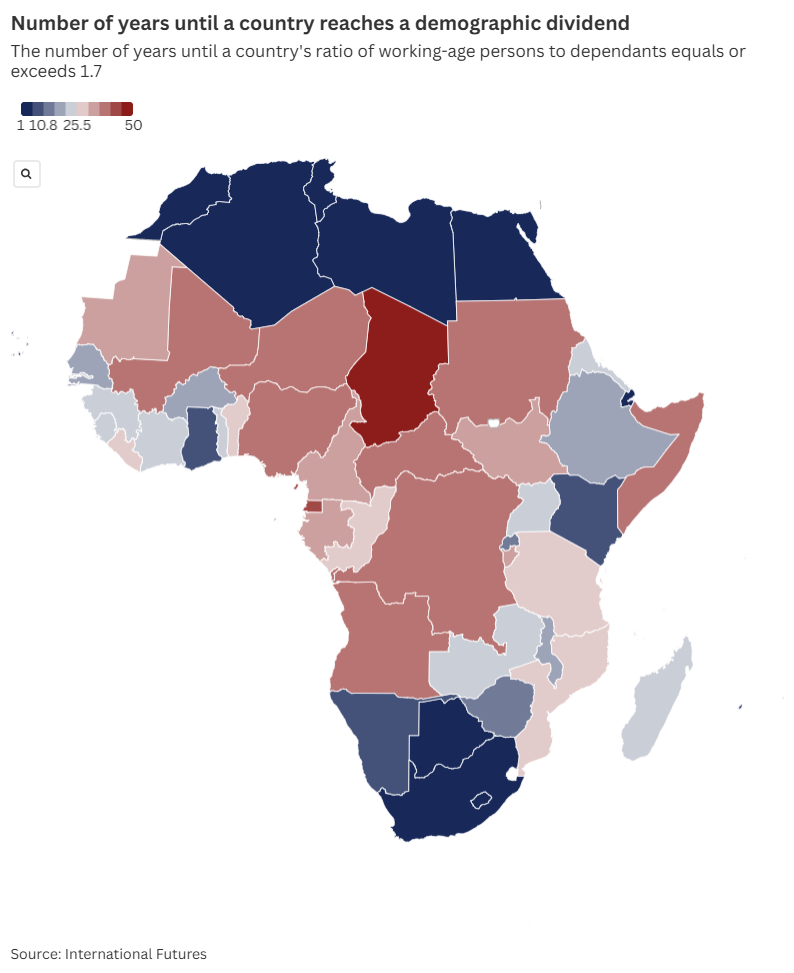

Even countries like South Africa and those in North Africa, which have more favourable demographics, struggle with low economic returns. In South Africa, rampant corruption, state dysfunction, and policy paralysis have overshadowed the benefits of a transitioning population.

Africa’s Missed Agricultural Revolution

Africa is often praised for its agricultural potential, yet most of the continent remains food-insecure. This is largely due to underinvestment in the agricultural sector, lack of mechanization, and outdated land policies. Rather than modernize agriculture, many governments continue to treat it as a political tool, handing out land and subsidies for political loyalty instead of productivity.

Corruption, again, plays a central role. Agricultural funds are frequently misappropriated, and rural infrastructure projects are left incomplete or overpriced. Youths, witnessing the poverty associated with farming, abandon the land for informal urban jobs, further weakening rural productivity.

The Demographic Window: Will Africa Be Ready?

According to the International Futures forecasting platform, sub-Saharan Africa may not enter a true demographic dividend window until around 2050, when the working-age population to dependent ratio reaches the magic number of 1.7:1. But by then, the rest of the world will have moved even further ahead – unless Africa addresses the governance deficit now.

To turn its demographic burden into a dividend, Africa must:

Tackle corruption head-on, not with lip service but with real accountability mechanisms.

Invest in quality education, particularly for girls and rural communities.

Improve access to reproductive healthcare and end child marriage to reduce fertility rates.

Diversify economies away from extractives and informal services into manufacturing, agribusiness, and technology.

Empower local governments and civil society to monitor public spending and hold leaders accountable.

Demography Is Not Destiny – Governance Is

Economic growth is not merely a matter of population statistics. It is about the quality of institutions, the integrity of leaders, and the effectiveness of policy. While it is true that rich countries tend to be better governed, that’s not because they were always wealthy – it’s because at some point, they made difficult choices, fought corruption, and built systems that rewarded merit and innovation over cronyism and theft.

Africa still has that choice to make.

If the continent can raise a generation of educated, skilled, and healthy young people while dismantling corrupt power structures, then the demographic boom will be a blessing. If not, Africa risks becoming the epicenter of global instability, with high unemployment, mass migration, and growing inequality.

The clock is ticking. Africa’s future depends not just on its people – but on how its leaders serve them.

Reference

Africa’s Development Crisis: A Demographic Burden or the Price of Corruption and Bad Governance?